Storm Water Predictor

I spent a few months working with OptiRTC, a smart storm water management company, developing an interesting computer vision application. Opti intelligently monitors and controls water levels in ponds, rivers and lakes in order to prevent flooding during storms. Currently, most storm water management systems rely on physical sensors in order to determine water height. As with any physical sensor system, these units are subject to failure due to lifespan and extraordinary conditions (such as freezes). Because these sensors are relatively expensive, it is difficult and costly to insure a back up measurement system. Thus, it is difficult to remotely determine if a site is functioning properly. Through my work with Opti, I developed a camera based water level measurement system, allowing for inexpensive and robust backup water measurement. Using Deep Learning techniques, I was able to produce a reliable pipeline for water level determination.

Stormwater management is a critical element of #SmartCities. Check out the video below to see how an Opti-controlled #stormwater pond performed during a recent rainfall event to improve water quality and reduce hydromodification impacts downstream pic.twitter.com/oOTkXbAsmI

— Opti (@OptiRTC) November 16, 2017

Storm water data is a perfect use case for Deep Learning and Convolutions Neural Networks (CNNs). As you can see in the examples above, the images are all of a similar feel, and the task of comparing water heights between pictures can easily be done by a human annotator. This suggests that there is a good chance we can train an algorithm do the same.

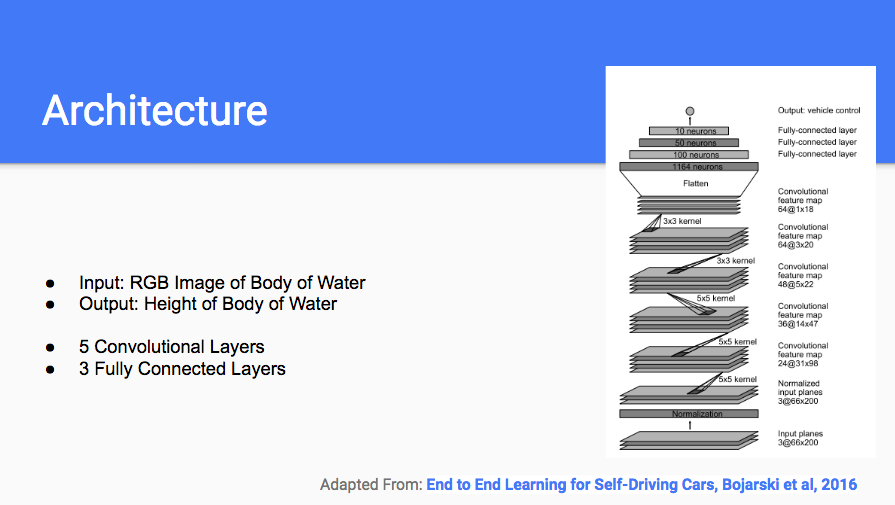

My goal was to create a model that could take, as an input, a photo of a pond, and determine the elevation of the pond’s surface (relative to an empty pond). By analyzing a large quantity of pond picture/water height pairs, I was able to train a model that was able to predict pond height reasonably well.

Briefly (See Technical Information for more), I used a convolutional neural network trained on 1000s examples from one pond site. On a high level this system works by taking a pond image, running the image through a set of numerical operations, and predicting a height. Then, based off of how close the prediction was to reality, the numerical operations are updated. In theory, as the algorithm sees more and more examples, it gets better and better at determining the exact height.

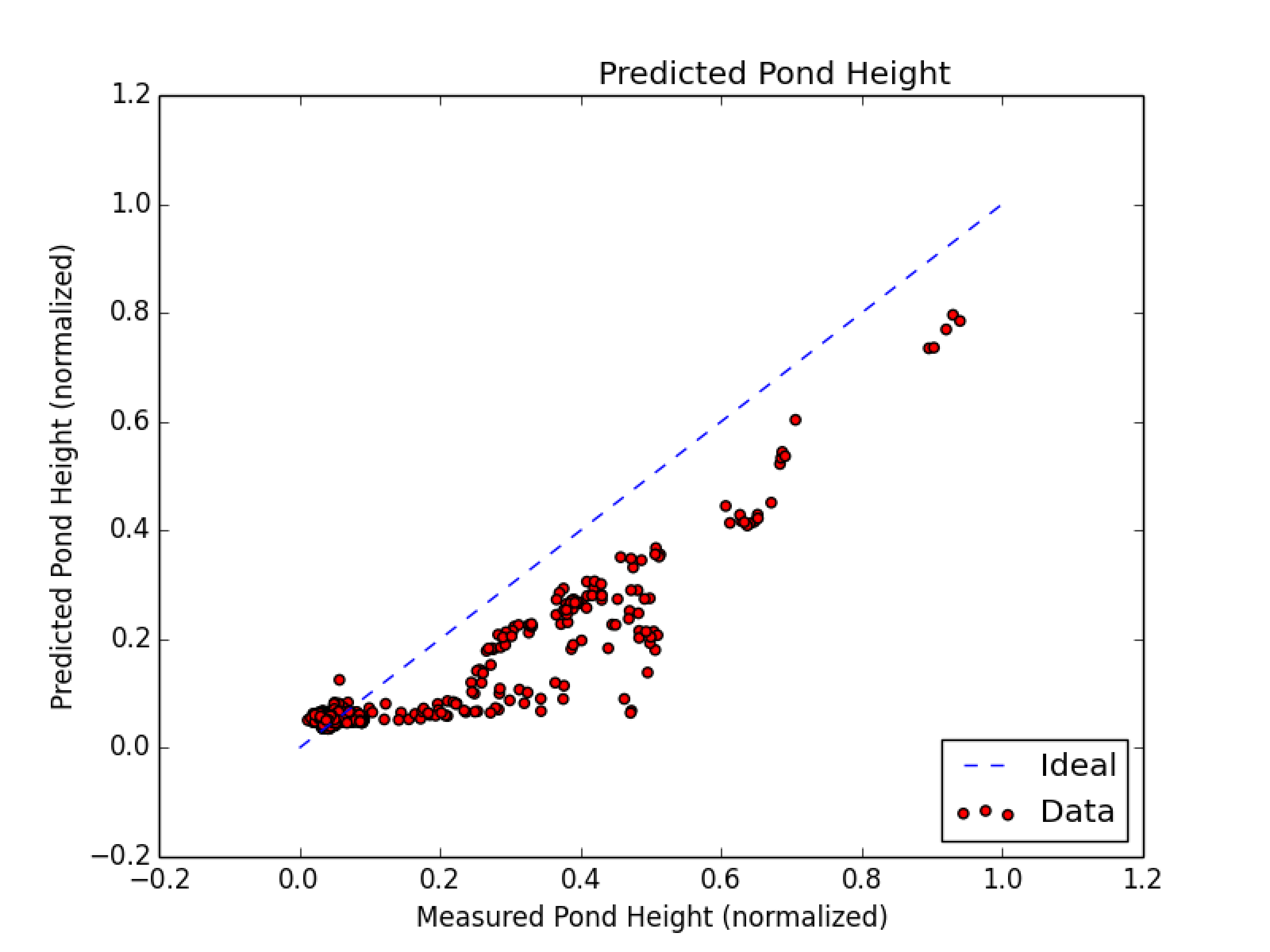

Looking at data from the site shown above in the video, a model was trained that reasonably predicted pond height from the videos. The chart below displays, showing the predicted pond height versus the real (measured) pond height. If the model was perfect, all points should be located on the dashed blue line. Though the model seemed to follow the proper slope of the line, it consistently predicted a height below reality. This was likely due to the fact that 80% of the dataset described an empty pond.

As you can see in the chart, a few data points are far from the ideal line. These data points represent pond conditions that are far from the norm, including both snow and night conditions.

This first investigation proved successful in demonstrating that a machine learning approach could be fruitful for water height measurement. Next steps would include; determining ideal network architecture for the current model, and pursuing a universal model that could be quickly applied to any body of water.

Technical Information:

The main goal of the first phase of this project was a sanity check, Can a CNN based model provide useful information for pond height predictions? Thus many of the design decisions were based off of quick prototyping.

As a first pass, I built a model similar to what I read about in a simple Self Driving Car paper [1], where the author was trying to predict steering wheel angle from a dash cam photo. I thought that the complexity of road images might be similar to that of pond images. The paper had delightfully open sourced a TensorFlow model, so I used that as a starting point for the pond model.

In this first pass vanilla version, I used an off the shelf loss functions and back propagation algorithms (Loss Function: L2 Loss + L2 Regularization, BackProp: Adam Optimizer, learning rate: 5e-4).

You can find the code on Github

[1] Mariusz Bojarski, Davide Del Testa, Daniel Dworakowski, Bernhard Firner, Beat Flepp, Prasoon Goyal, Lawrence D. Jackel, Mathew Monfort, Urs Muller, Jiakai Zhang, Xin Zhang, Jake Zhao, and Karol Zieba. End to end learning for self-driving cars, April 25 2016. URL: http://arxiv.org/abs/1604. 07316, arXiv:arXiv:1604.07316.

Header photo © OptiRTC 2018

Icon photo © Sam Woolf 2018

Body video © Sam Woolf 2018

Body Charts © Sam Woolf 2018